Analysis

Analysis is taking something apart to see how it works. In this class (and in your portfolio), the goals of this analysis are both to demonstrate your ability to talk about your writing, but also, show your ability to practice deliberatively. What is deliberate practice? It’s sustained cognitive and associative effort on a given task towards improvement in that task. In the original study on practice, Ericcson et al. (1993) studied violin players, but subsequent studies have looked at everything from playing chess to typing. Malcolm Gladwell (2008) made Ericcson more famous by sharing what has become the infamous 10,000 hour rule (interesting enough, if you Google “10,000 hour rule,” you will get Gladwell’s name rather than Ericcson, even though it’s Ericcson’s study).

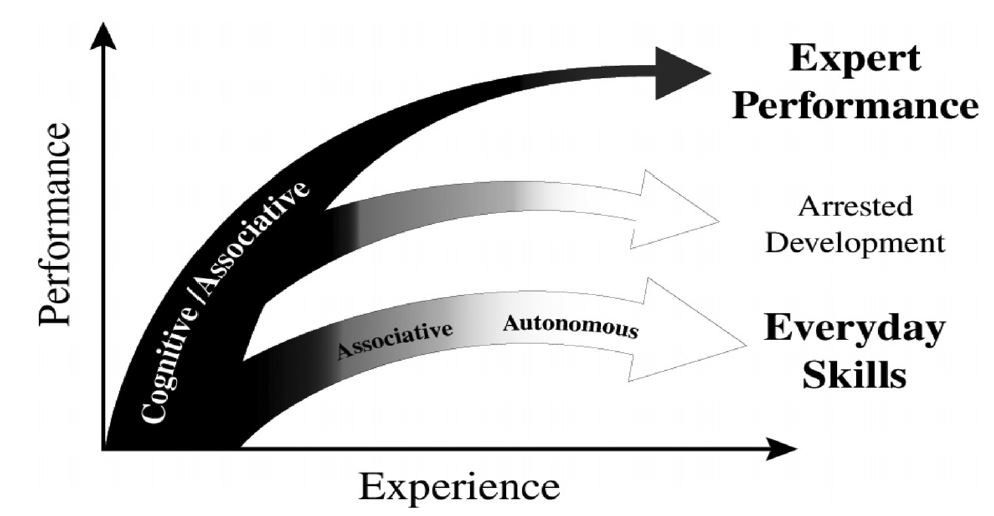

What does this have to do with writing? To put it plainly, you already know how to write. You were able to graduate high school, enter a selective university, and since, have proved your ability to navigate a variety of writing tasks. Along the way, you have received feedback, been given new challenges that asked you to think in different ways, and asked to reflect and improve your writing. However, what happens after you graduate, and you have to write the same TPS report over and over again? In writing, deliberate practice asks that you create space for yourself to reflect and perform novel tasks that help you improve. Take a look at this chart from Ericcson (2006):

You will note that it is easy to fall into autonomous performance. A good analogy is driving. Imagine how many hours that you have driven, to and from school or work, to a friend’s house, to a concert or movie. You are probably a confident driver with many hours of practice. However, let’s imagine that you and NASCAR racing legend Jimmie Johnson were to race against each other, both using the same type of car. Who would win? The difference is that driving has become an autonomous skill to you because that level of skill is sufficient for what you use that skill for. For Jimmie Johnson, he has to constantly practice to be the best. Writing is like driving. There are some tasks that are probably autonomous: sending a text to a friend, writing a to-do list, and maybe even writing a particular type of essay or answering a short answer question on a test. To get better, you have to engage in deliberate practice.

So what constitutes deliberate practice in writing? We can point to a few conditions. The first is feedback. Whether from a teacher, a friend, a boss, or an editor, feedback leads us to improve by helping us see things differently. Second is navigating a variety of rhetorical tasks. Communication through short stories, poems, infographics, essays, proposals, lab reports, blog posts, and research studies makes us better writers than if we just wrote essays for four years. Finally, there is reflection. That is, going back to our writing and thinking about the decisions we made.

Two notable types of practice are useful here: making purposeful choices and multiple perspective reflection.

As you write, think of the proportion of the words and sentences that you purposefully chose to that of words that seem to fill themselves in to connect ideas. If you find that the words you use are mostly just rote performances, you are writing autonomously. In the Deconstruction assignment here, you will be revisiting one piece of writing and describing how you did what you did and why—describing your purposeful choices to uncover those choices.

Reflection, on the other hand, asks you to consider what you are learning about writing from writing. Reflection is not an activity in and of itself. That is to say, the act of reflection ends, and we presumably are smarter and able to move on to a new task—it doesn’t work that way. A useful reflection asks a person to think about the future as well as the past (Robertson, Taczak, and Yancey, 2012). In the Reflection, you will be revisiting one of your portfolio pieces and looking inward, outward, backward, and forward.

So why is this important? Because literacy practices always shift. Autonomous driving has been working because the operation of a motor vehicle and the rules of the road have changed very little (until we have autonomous vehicles so that we won’t even need autonomous driving skills anymore). However, writing tasks are constantly changing. Blogging wasn’t a common genre until a decade ago, and Twitter and Facebook are similarly less than a decade old. There’s no written genre that is futureproof. Engaging in deliberate practice allows you to become more agile in adapting to the constant change that will occur in your lifetime. While work on reflection in deliberate practice has been around for awhile, notably from Dewey (1910) and Schon (1984), I want you to read a chapter from The Age of Unreason by Charles Handy. Writing in 1989, Handy foresaw the now common practice of the divested workplace and the need for individuals to live a “portfolio life.” In other words, the chance of going to one company to work at the same job doing the same task (and the same type of writing) for the rest of your life isn’t a reality that you will know. You have a number of different skills that you can highlight in a variety of working conditions, and you will collect those skills as your portfolio that will build over time.

The objective this week is to showcase your expertise in writing by having you show that your written work is a result of deliberate practice and conscious expertise—in other words, your work isn’t just autonomous performance. You will feature ONE of these analyses (either the Deconstruction or the Reflection) in your final portfolio. However, you will still write both this week in the class.

Reading This Week

- Charles Handy The Age of Unreason (chapter 3, ≈5,700 words, about 45 minutes to read)

Design this Week

- Deconstruction [due Wednesday, 11:59pm]

- Reflection [due Friday, 11:59pm]